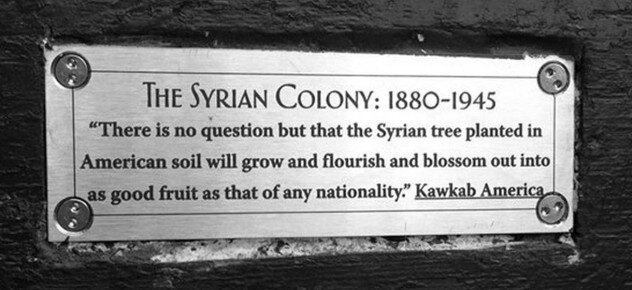

History of the Syrian Colony of Manhattan

The Sacred tells the story of the Syrian neighborhood located at the foot of Manhattan and the transformations it has undergone.

"Syrians," from both present-day Lebanon and present-day Syria,

began immigrating to the United States around 1880. They came for a number of reasons—both “push” and “pull.” Many were drawn by the opportunities they thought awaited them in America, introduced to them by American missionary schools in Lebanon and Syria.

Others were affected by a drastic fall in silk prices, which devastated many communities in Mt. Lebanon forcing them to seek their fortunes elsewhere. Still others went for that age-old reason: adventure.

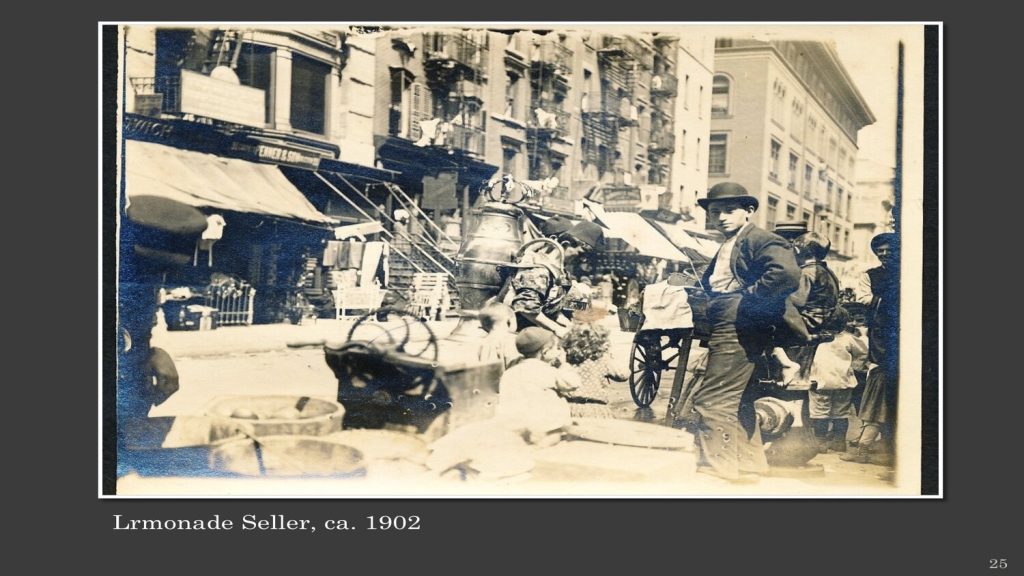

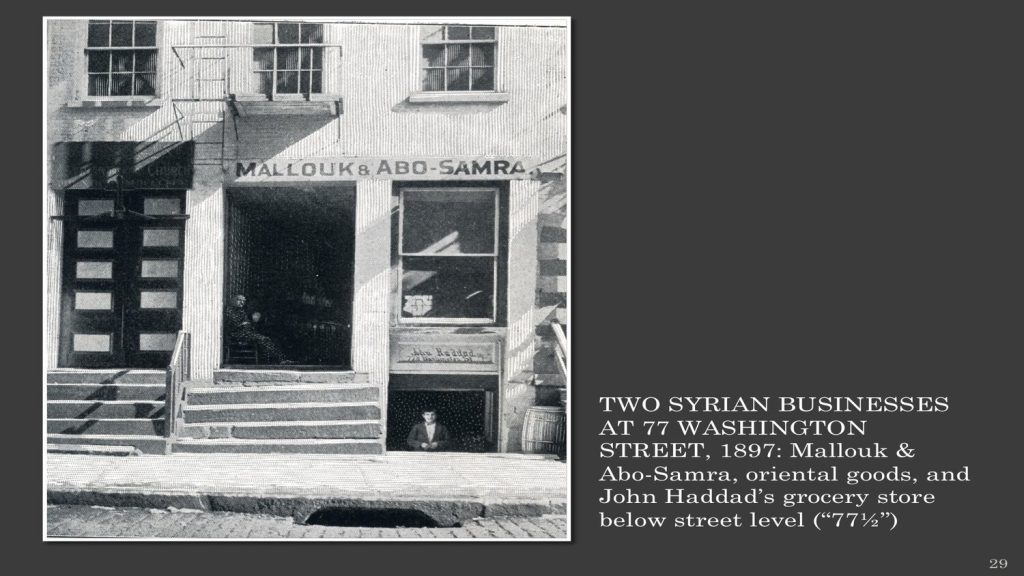

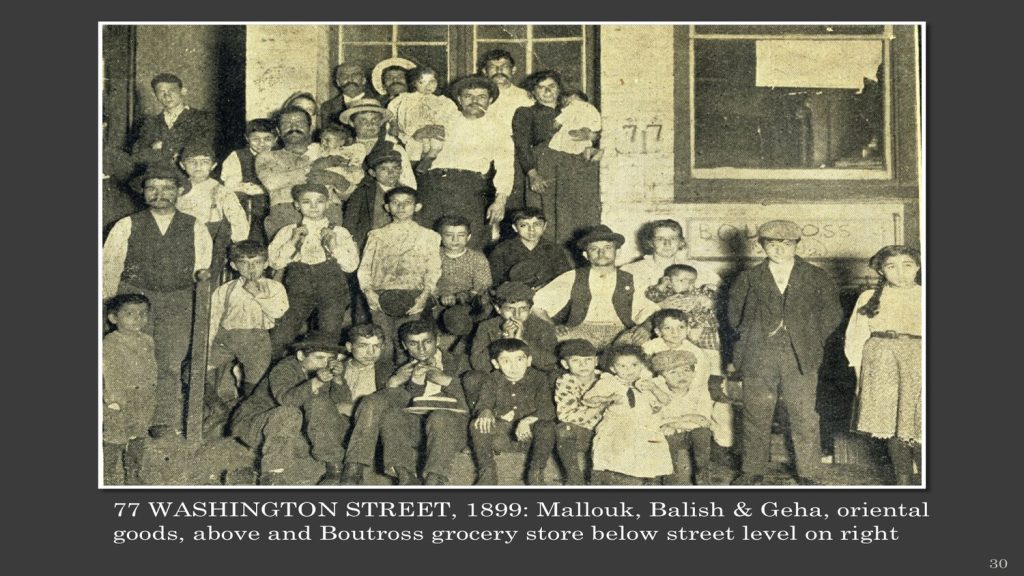

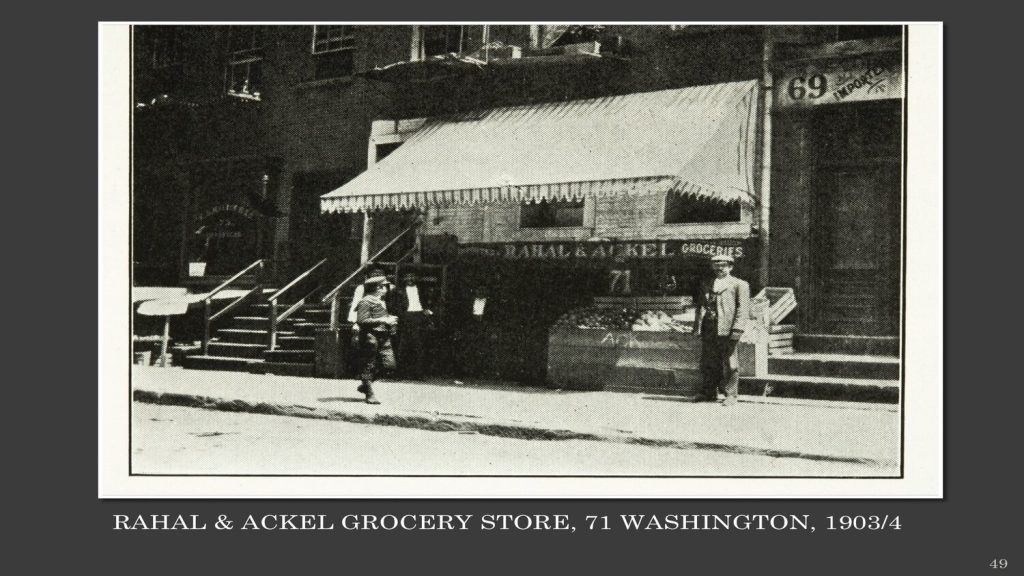

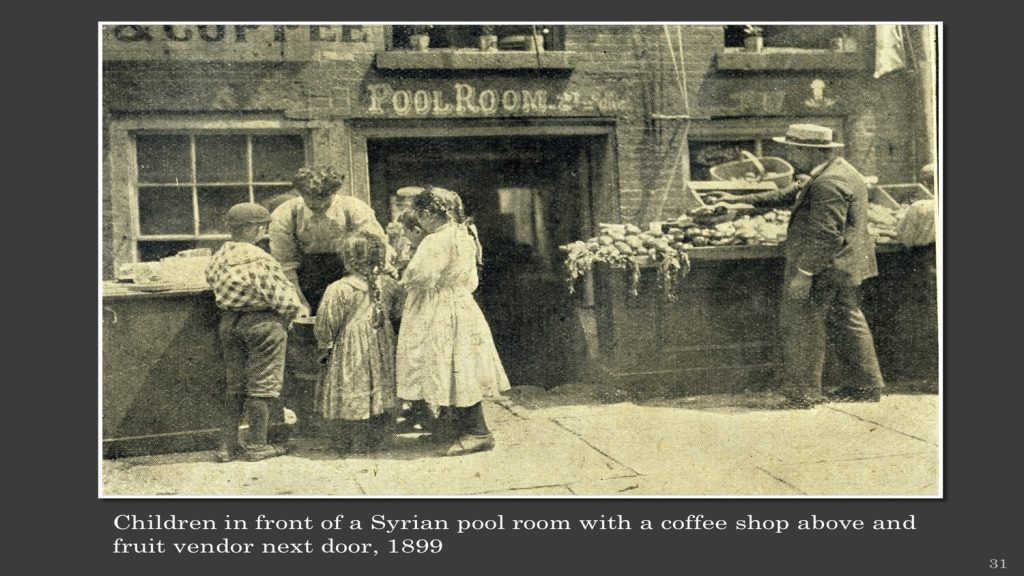

After an arduous three-week journey from the eastern Mediterranean, they disembarked at Battery Park at the southern tip of Manhattan and walked a few steps to the foot of Washington Street, where they settled in tenements already populated by Irish and German immigrants. Washington Street became the center of the Syrian colony. Up and down the street, from the Battery to Albany Street, Arabic was heard as often as English, Arabic signs appeared on dozens of storefronts, men might still be wearing the fez of their homeland, and restaurants served familiar food. New Yorkers ventured downtown to see these “exotic” new residents.

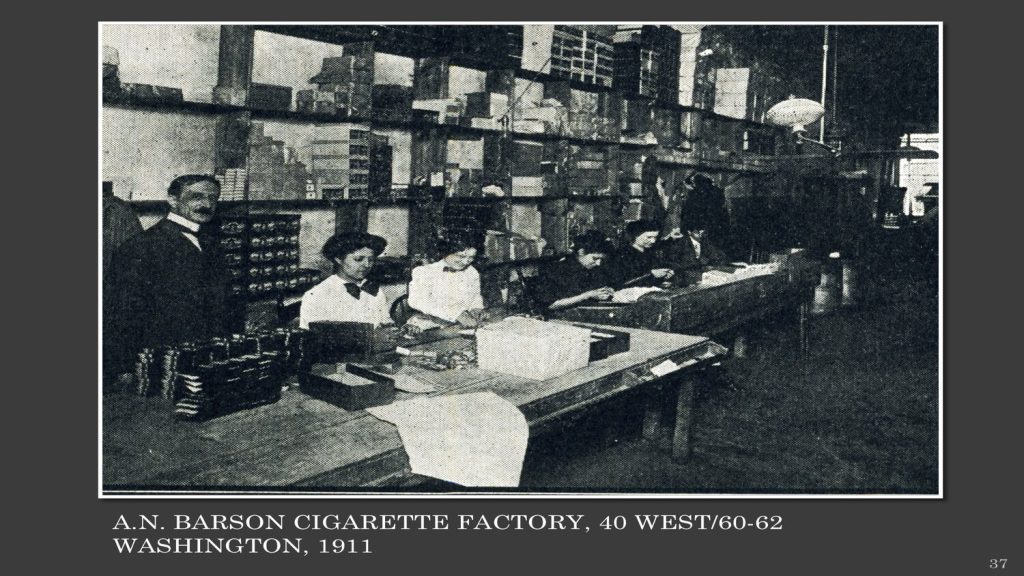

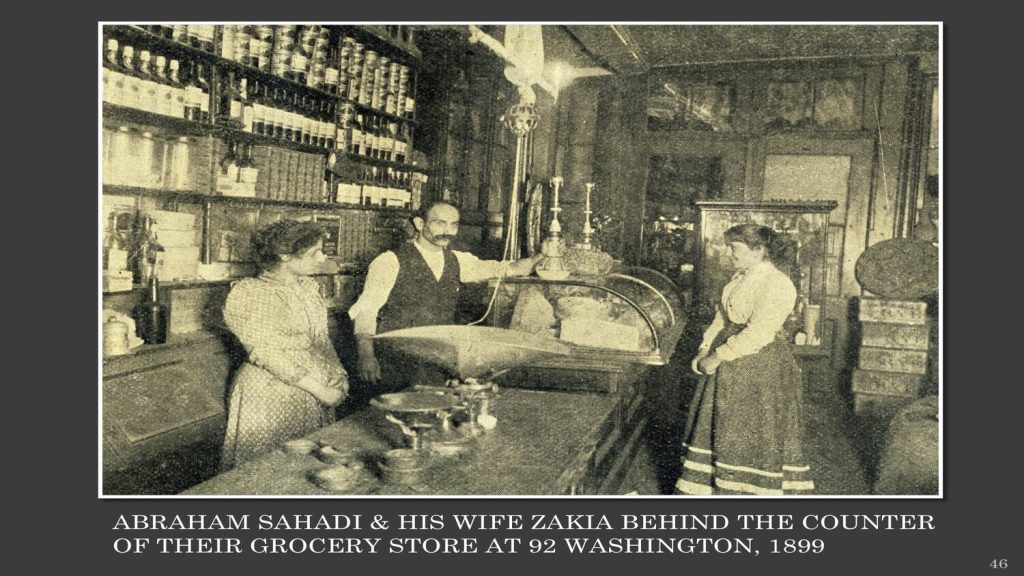

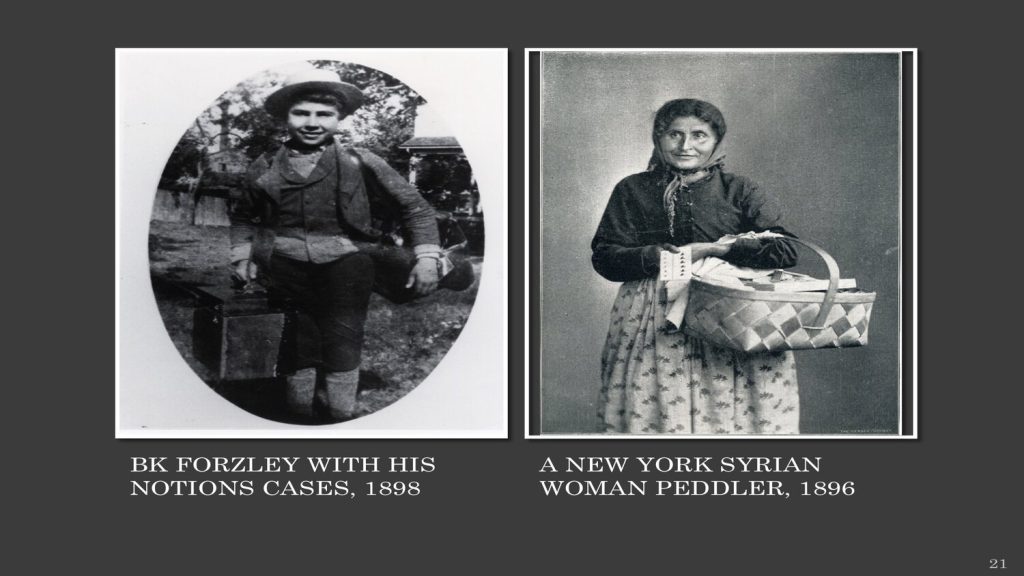

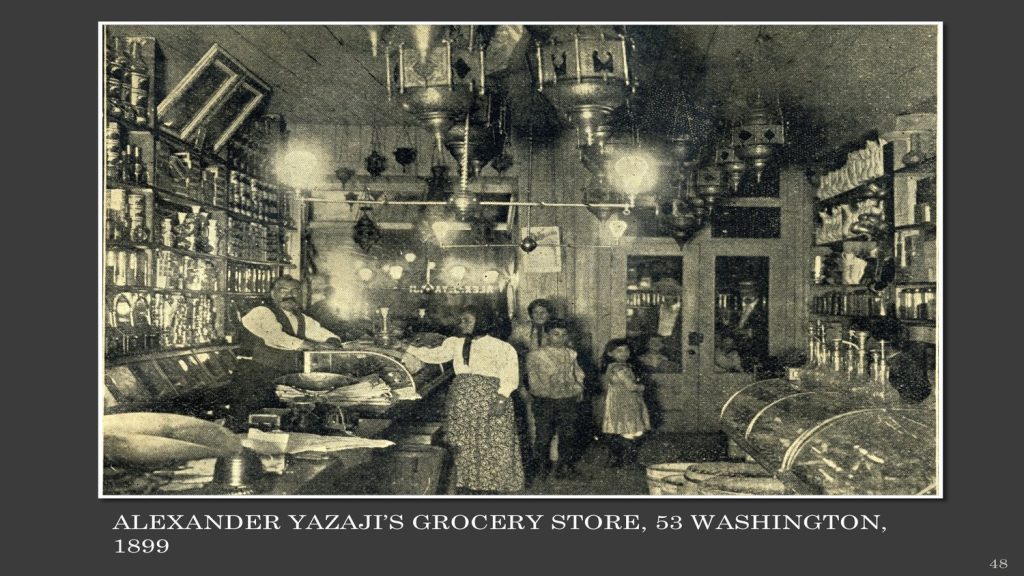

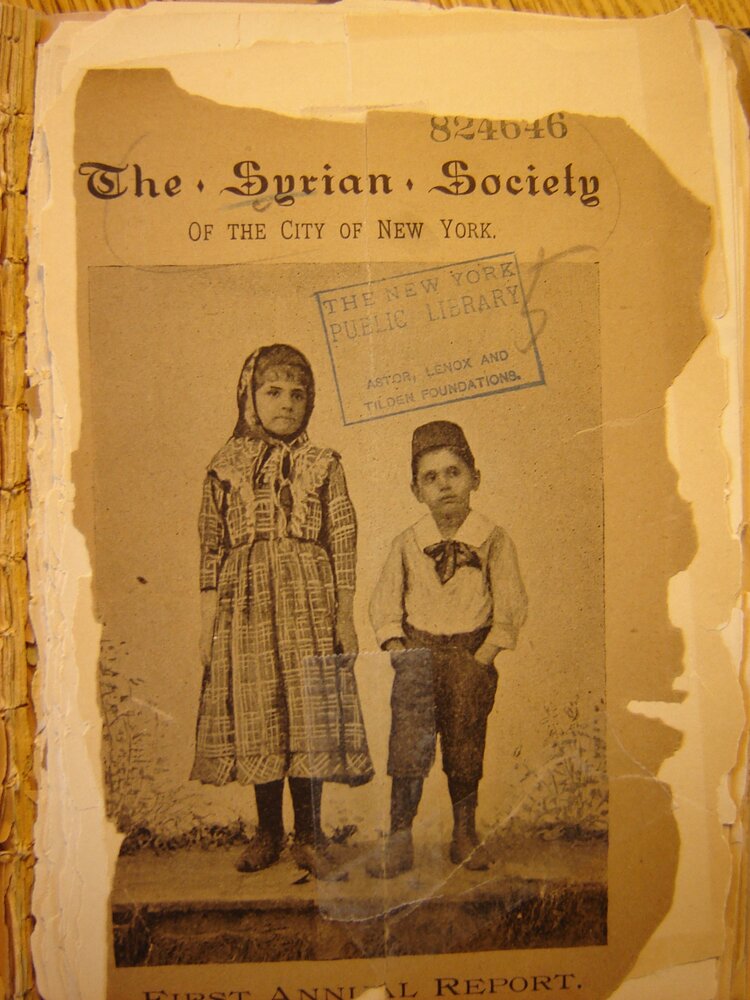

Around 1,500 Syrians were living in New York City in 1900. Crowded into tenements every bit as dismal as those on the better-known Lower East Side, the Syrians nonetheless built a thriving economy, first peddling notions and Holy Land goods, then becoming merchants. They supplied goods to their countrymen—and women—and also sold exotic Middle Eastern items meant to satisfy the Orientalist obsession that took hold of America in the late nineteenth century.

What Business Are You In?

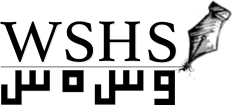

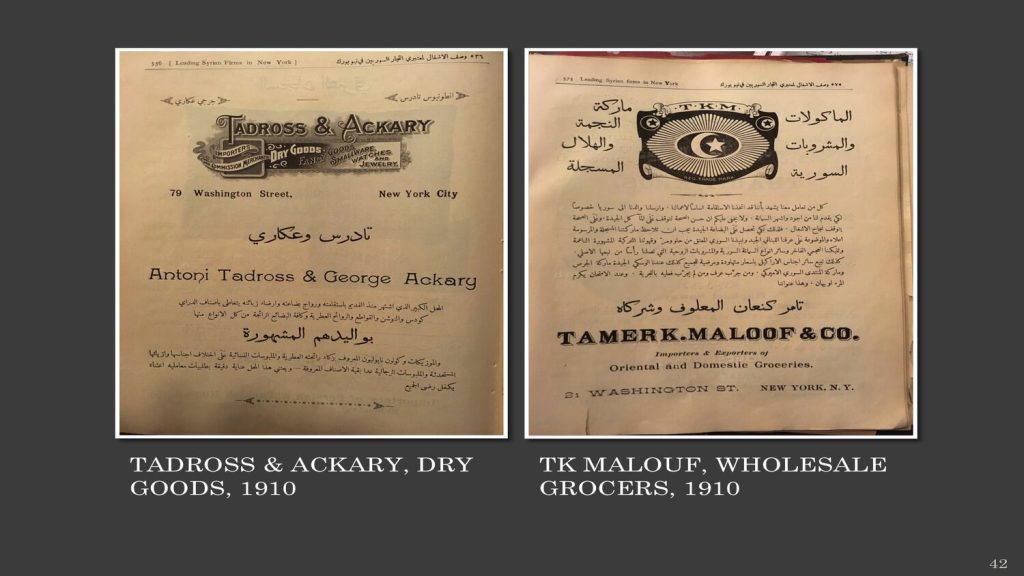

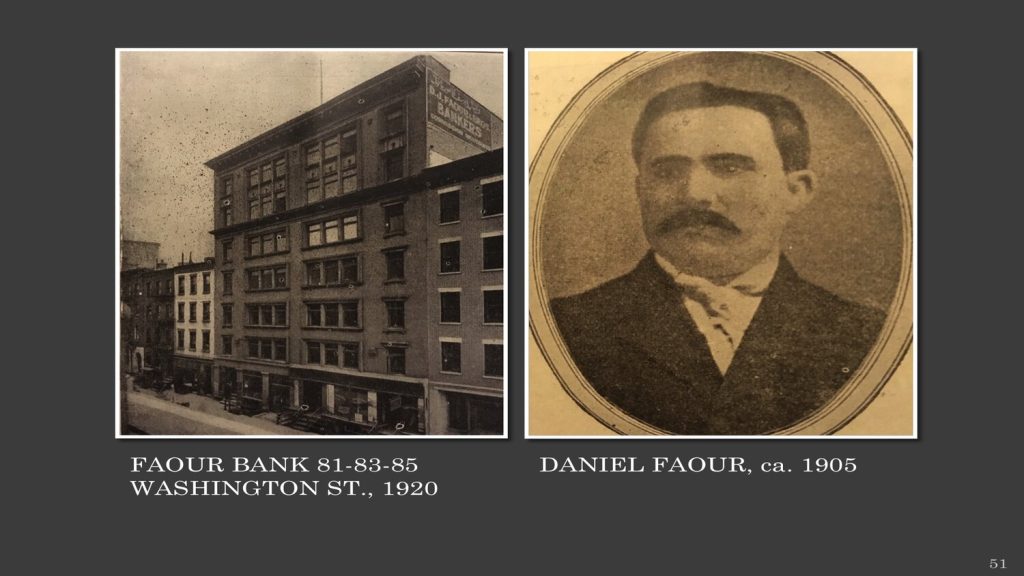

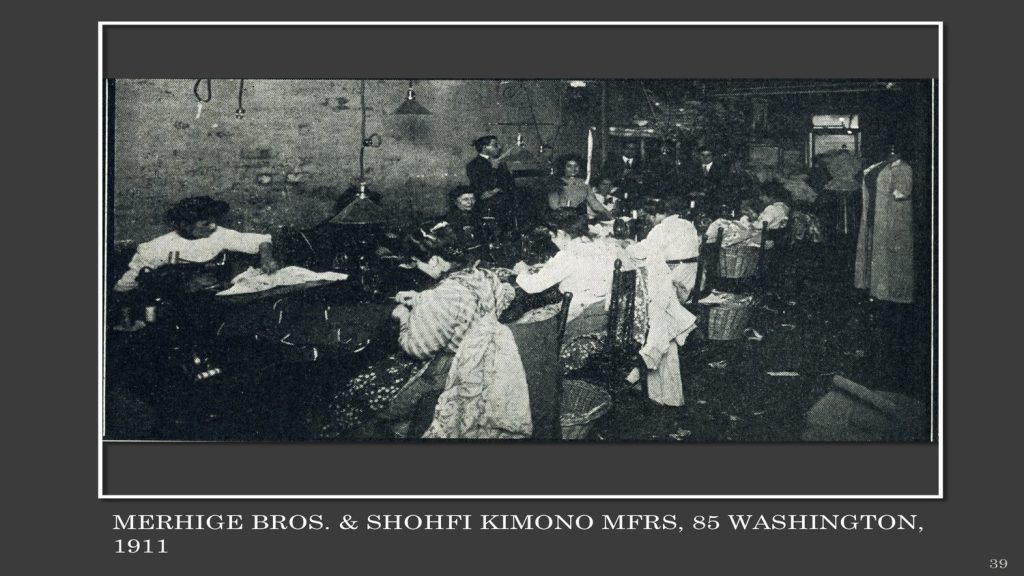

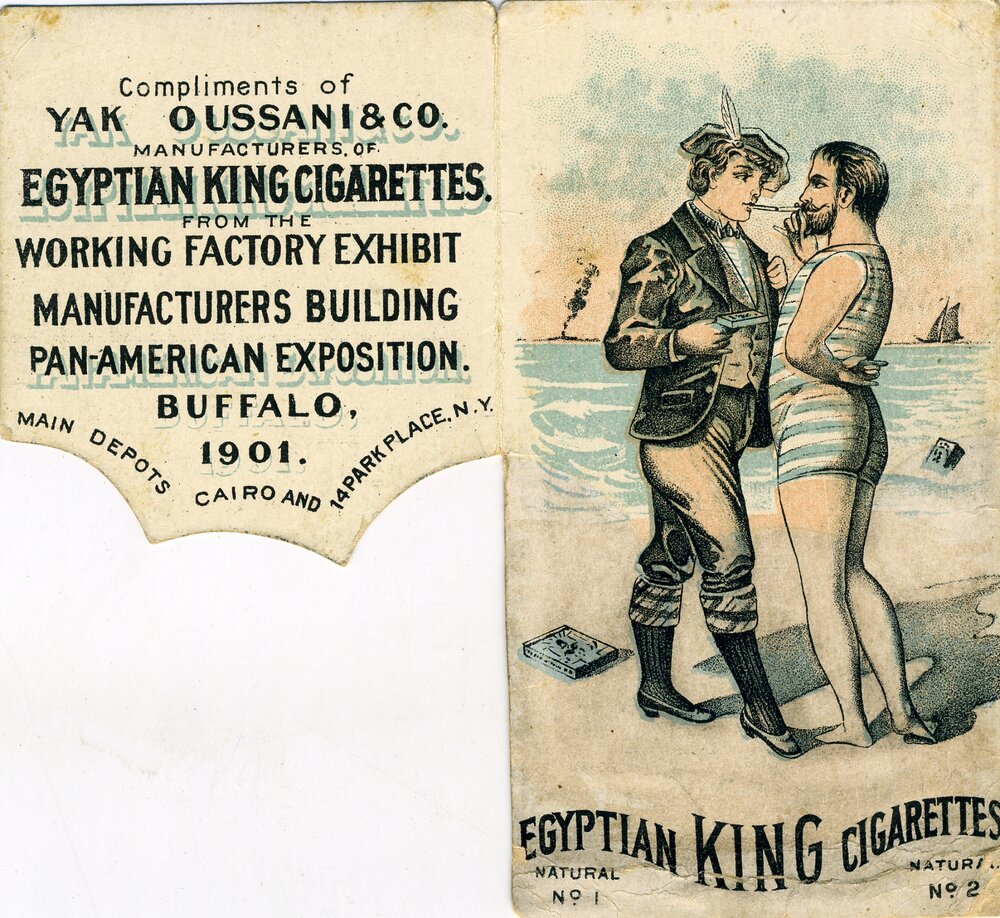

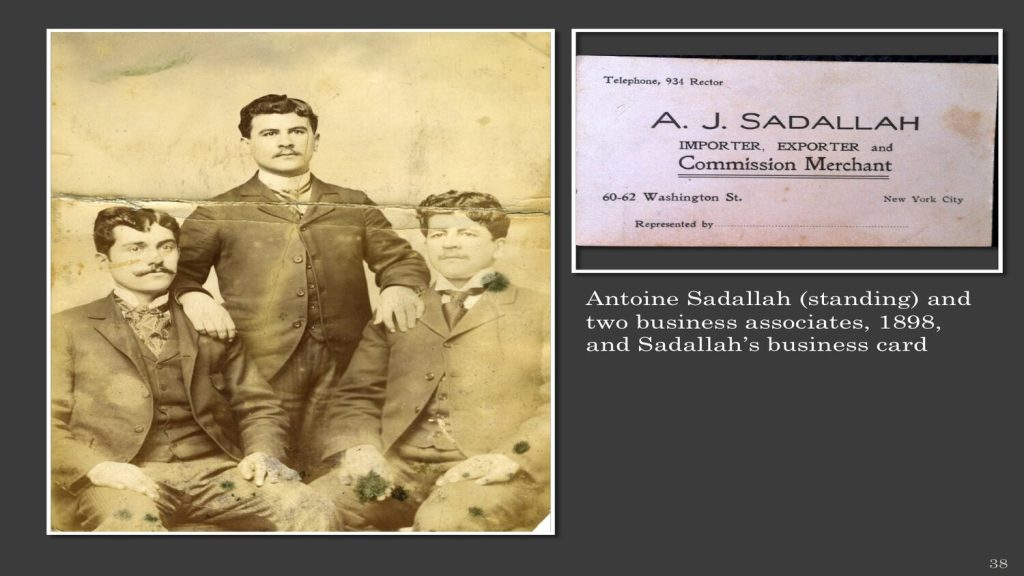

Being self-employed was the ideal, and the entrepreneurial spirit was strong. Although they started off as peddlers, they quickly set up wholesale businesses or went into the import-export trade, depending on a worldwide network of Syrian merchants. Syrian-owned workshops produced dressing gowns, kimonos, “waists,” or lace. Cigarette factories hired Syrian women, whose small hands were more adept at rolling. “Turkish smoking parlors” were the bright idea of an Iraqi entrepreneur who opened the first one in 1895; by 1900 dozens were in operation in New York. These smoking parlors catered to women and made it respectable for women to smoke in public. Although women, like men, had been peddlers, most stopped working after marriage, but some continued to work in Syrian-owned factories, small mom-and-pop shops, or as midwives or merchants.

Some of the early immigrants came armed with a university education, including some with medical degrees from Syrian Protestant College (today’s American University of Beirut). Many were literate in Arabic and/or English and began to publish Arabic newspapers, the first of which appeared in New York in 1892. The work of poets and writers appeared in newspapers before there was a publishing industry, but by the first decade of the twentieth century, books of poetry, essays, and novels in both Arabic and English began to appear. The Pen Bond, founded in 1916 and again in 1920 by ten poets and writers, was the literary apogee of the colony.

The great majority of those who came were Christians: Maronites (Lebanese Catholics), Melkites (Greek Catholics), Orthodox, and a sprinkling of Protestants, although a few Muslims and Druse were no doubt present. They attended American churches until they could bring over their own Arabic-speaking priests, the first of whom arrived in 1890; others followed in short order. The priests raised money from their respective congregations to convert Washington Street loft spaces into chapels, where Sunday services and baptisms and weddings took place.

Around the turn of the century,

prosperous Syrians began to move their families to Brooklyn, where the accommodations were cleaner, larger, and cheaper, and from where the ferry ride to lower Manhattan was cheap and easy. The Brooklyn South Ferry colony became known as “Little Syria.”

This did not mean Washington Street was abandoned; far from it. New Syrian immigrants flooded in, still living in the same miserable conditions as their predecessors until they too could move up and out. Syrian businesses remained on Washington Street for decades, even after their owners had moved to Brooklyn.

With the ever-more-onerous restrictions on immigration, however, culminating in the Quota Law of 1924, the number of Syrians allowed to immigrate was cut drastically, causing a decline in the size of the community. Newcomers from other countries, particularly Eastern Europe, settled in the neighborhood in their stead; in 1917, a reporter counted twenty-seven nationalities among the residents. The tenements and old low-rise businesses gradually gave way to encroaching skyscrapers, and in 1946, eviction notices were handed to the last remaining residents, as the buildings on lower Washington Street were slated for destruction to build the Brooklyn Battery Tunnel. Only three buildings were spared, 105-109, which activists have been trying to preserve for over a decade.